In this practice guideline

Regulation 82: Parent and divisional claims “for substantially the same matter”

This guideline outlines IPONZ’s practice on parent and divisional claims “for substantially the same matter” under regulation 82.

Regulation 82

82 Acceptance of complete specification

The requirements prescribed for the purpose of section 74(1)(b) of the Act are—

(a) to pay any fee and penalty that has become due under the Act or these regulations; and

(b) in the case of a divisional application, if the Commissioner has accepted the complete specification relating to a parent application, that the divisional application must not include a claim or claims for substantially the same matter as accepted in the parent application; and

(c) in the case of a parent application, if the Commissioner has accepted the complete specification relating to a divisional application, that the parent application must not include a claim or claims for substantially the same matter as accepted in the divisional application.

Introduction

1. Regulation 82 prohibits the Commissioner from accepting an application which includes claims for substantially the same matter as that already accepted in a divisional or parent application. In this guideline we refer to this as “prohibited overlap” or claims “for substantially the same matter”.

2. Claims for substantially the same matter in a parent and divisional is prohibited because there shouldn't be two patents granted to the same person which claim the same invention. This is undesirable and there is no justification for two patents being granted for the same invention. 1

3. The prohibition of parent and divisional overlap has a long history. The Patents Regulations 1954 similarly prohibited overlap. 2

4. Practice regarding claims “for substantially the same matter” in a parent and divisional examined under the Patents Act 2013 is informed by Oracle International Corporation [2021] NZIPOPAT 5 (“Oracle”) 3 and Ganymed Pharmaceuticals GmbH et al. [2021] NZIPOPAT 6 (“Ganymed”). 1

When regulation 82 applies

5. Regulations 52 and 82 were amended on 5 April 2018. 4 This was to clarify that overlap is considered during examination. An application does not need to be free of prohibited overlap at filing. The practice in relation to considering overlap is otherwise unchanged between regulations 52 and 82.

6. Applications submitted prior to 5 April 2018 will be considered under regulation 52. Applications submitted on or after this date will be considered under regulation 82. 5

7. For brevity this guideline refers to regulation 82. This may be used interchangeably with regulation 52 where applicable.

What applications regulation 82 applies to

8. Regulation 82 only refers to a parent and divisional application. The intent of this regulation however is to prevent two or more patents being granted for the same invention. 1

9. IPONZ considers that regulation 82 is applicable to any application within the same divisional patent family. That is, any application that is linked by a divisional chain back to a single New Zealand parent application.

10. Therefore, examiners will consider any application that is within the same divisional patent family. This includes grandparent, parent, sibling and child applications of the application under examination.

11. A formal objection will only be raised when there is prohibited overlap with an application that has been accepted.

12. An informal notice may be raised to make the applicant aware of prohibited overlap with other applications that have not yet been accepted.

13. Formal objections and informal notices may be raised against multiple applications within a patent family when appropriate.

14. It’s in the applicant’s best interests to address and resolve objections and informal notices regarding prohibited overlap as soon as reasonably possible. If an informal notice isn't addressed and both applications are approaching acceptance, IPONZ will not allow both applications to proceed to acceptance.

Meaning of ‘substantially the same matter’

15. Substantially the same is defined as “essentially the same”, “the same but for minor unimportant details”, and/or “not substantially different”. 6

16. This means that claims may have some differences while still being to substantially the same matter.

Regulation 82 is directed to the scope of the claims

17. Consideration of the claims of a parent and divisional under regulation 82 is directed to the scope of the claimed invention. This is discussed in Oracle where it clarifies that reference to “a claim for matter” in regulation 82 is directed to “the scope of the claimed invention”. 7

Double infringement test

18. The “double infringement” test 8 for assessing overlap asks:

- Would an infringement of the claim(s) of the first application also be an infringement of the claim(s) of the second?

- And would an infringement of the claim(s) of the second application also be an infringement of the claim(s) of the first?

19. If the answer to both questions is yes, then the claims are considered to be “for substantially the same matter” and prohibited overlap is present.

20. When applying the double infringement test, the claim(s) are to be construed as they would be understood by the person skilled in the art. Further, as discussed at paragraph [17], it is the scope of the claims that is to be considered when applying the double infringement test.

21. The term “an infringement” in the double infringement test is therefore taken to mean “all infringing embodiments” that fall within the scope of the claim, not just any “single infringing embodiment”. If there are infringing embodiments within the scope of one claim which are not within the scope of the other claim, this will not meet both arms of the double infringement test.

No discretion to allow overlap

22. The Commissioner does not have any discretion under regulation 82 to allow claims in a parent and divisional application to cover "substantially the same matter", due to the wording “must not”. 9 Therefore, when there is prohibited overlap an objection must be raised.

23. In contrast, regulation 23(2) of the Patents Act 1953 allowed the Commissioner discretion regarding overlap due to the wording “may require such amendment”.

24. Discretion under regulation 23(2) was whether to object and require amendment of the claims. Where amendment was deemed to be inappropriate, the Commissioner could decide to not object. This discretion was not in how overlap was assessed.

25. See Abbott Laboratories [2003] NZIPOPAT 16 10 and Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research et al [2009] NZIPOPAT 21 11 for decisions under regulation 23(2) of the Patents Regulations 1954 which discuss the application of discretion in more detail.

Overcoming an objection to “substantially the same matter”

26. Following Ganymed 1 , an objection under regulation 82(b) or (c) may be overcome by:

- Providing a persuasive objection response, or

- Amendment of the relevant application(s) to remove prohibited overlap (either pre-acceptance or post-acceptance), or

- Withdrawal of the accepted application, or surrender of the granted patent.

Relevant case law

27. Two IPONZ Hearings Office decisions on aspects of regulation 82 inform current examination practice.

Oracle International Corporation [2021] NZIPOPAT 5 (“Oracle”) 3

28. The Assistant Commissioner considered parent and divisional claims with similar but not identical wording.

29. In the decision, the Assistant Commissioner:

- Established the “double infringement” test for assessing overlap (see paragraphs 18-21 above); 8

- Provided a definition of “substantially the same” (see paragraph 15 and 16 above); 6 and

- Confirmed that the Commissioner has no discretion to allow claims in a parent and divisional application to cover substantially the same matter (see paragraph 22 above). 9

30. The Assistant Commissioner upheld the objection under regulation 82, finding that despite minor differences in wording, the claims of the parent and divisional were identical in scope and so met the double infringement test.

31. The decision emphasizes that the claims must be construed as they would be understood by a person skilled in the art. If the skilled person would consider all infringing embodiments of a claim of the first application to infringe the second, and vice versa, the requirements of the test are met. 8

Ganymed Pharmaceuticals GmbH et al. [2021] NZIPOPAT 6 (“Ganymed”) 1

32. The Assistant Commissioner considered whether post-acceptance changes could overcome an objection under regulation 82.

33. The applicants’ surrender of the parent patent was found to overcome the objection.

34. This decision clarified IPONZ’s practice in two aspects:

- When overlap is to be considered under regulation 52 versus 82 (see paragraphs 5 and 6 above); 5 and

- That withdrawal of an accepted application (or surrender of a granted patent) can overcome an objection to prohibited overlap (see paragraph 26 above). 12

IPONZ approach to examining overlap

35. The approach to considering overlap during examination is to first make an initial assessment of the patent family.

36. The purpose of the initial assessment is to identify any claims that require further consideration to see if they are to “substantially the same matter”.

37. The initial assessment will not typically be included in the examination report. The steps of this assessment will depend on the circumstances of the case.

38. This initial assessment generally includes a comparison of all claims of the application being examined and the claims of all applications within the same divisional patent family. The dependent claims may be relevant where they are closer in scope than the main independent claims.

39. From this initial assessment, the claims which are most similar in scope are identified for further comparison. If no claims are identified from the initial assessment, then no formal comparison is required.

Double infringement test

40. The test used to assess overlap is the double infringement test.

41. A claim comparison table can be used to compare claims of the respective applications.

42. Claims will be assessed as they would be understood by the person skilled in the art.

43. For the purpose of applying the individual arms of the double infringement test, the infringement being considered includes all recited features of the respective claim. This is then compared to the corresponding claim to consider if there would be infringement.

44. Where the person skilled in the art would understand that all infringing embodiments of the first claim would infringe the second, and all infringing embodiments of the second claim would infringe the first, it is considered that the claims are “for substantially the same matter”.

45. As there is no discretion under regulation 82, if prohibited overlap is found using the double infringement test, an objection must be raised.

Objecting to prohibited overlap

46. An objection under regulation 82 needs to identify which claims are being objected to and which claims of the other application are considered to be “for substantially the same matter”.

47. This may be done by including a claim comparison table where appropriate.

48. The exception to this is where prohibited overlap is readily apparent prima facie. For example, a whole of contents divisional applications where the parent claims are clearly derived from the original claim set may be objected to more generally.

Examples

Example 1

Parent

Claim 1. A mobile vehicle that includes a camera configured to capture a two-dimensional image, and a processor configured to determine the presence of an obstacle by analysing the two-dimensional image and to generate a control signal of the mobile vehicle.

Divisional

Claim 1. A mobile vehicle that comprises an imaging means that captures a 2D image, and a processing means that analyses the captured image to identify an obstacle, where a command for controlling the mobile vehicle is generated based on the identified obstacle.

The claims are compared below:

|

Parent claim 1 |

Divisional claim 1 |

|---|---|

|

a mobile vehicle |

a mobile vehicle |

|

a camera configured to capture a two-dimensional image |

an imaging means that captures a 2D image |

|

a processor configured to determine the presence of an obstacle by analysing the two-dimensional image and to generate a control signal of the mobile vehicle |

a processing means that analyses the captured image to identify an obstacle, where a command for controlling the mobile vehicle is generated based on the identified obstacle |

In view of the complete specification, the person skilled in the art would construe the “imaging means” and the “processing means” as claimed in the divisional as being substantially the same as the “camera” and the “processor” of the parent claim.

Applying the double infringement test, all infringing embodiments of the claim of the parent would infringe the divisional claim; and all infringing embodiments of the claim of the divisional would infringe the claim of the parent. Therefore, the claims are considered to be for substantially the same matter and an objection would be raised.

Example 2

Parent

Claim 1. A system for providing breathable gas to a patient including:

- a mask including a gas inlet port and a cushion for surrounding a patient’s airway/s;

- a blower for delivering the gas to the mask; and

- a hose for connecting the blower to the mask.

Claim 2. The system according to claim 1, where the cushion includes ports for fluid communication with the patient’s nares and the cushion surrounds the periphery of the underside of a patient’s nose.

Divisional

Claim 1. A mask for surrounding and providing air through a patient’s nostrils including:

- a cushion for surrounding the periphery of the underside of a patient’s nose; and

- a port for connection to a conduit for providing air of ambient pressure or above.

Claim 2. A system for providing air through a patient’s nostrils including:

- a mask according to claim 1 wherein the cushion includes two openings for aligning with the patient’s nostrils;

- a blower for delivering the gas to the mask; and

- a conduit for providing air of ambient pressure or above between the blower and the mask.

The closest claims identified in the initial assessment are claim 2 of the parent and claim 2 of the divisional.

The claims are compared below:

|

Parent claim 2 |

Divisional claim 2 |

|---|---|

|

a system for providing breathable gas to a patient |

a system for providing air through a patient’s nostrils |

|

the system includes a mask, a blower and a hose |

the system includes a mask, a blower and a conduit |

|

the mask includes… …a gas inlet port and …a cushion for surrounding a patient’s airway/s |

the mask includes… …a port for connection to a conduit for providing air of ambient pressure or above …a cushion for surrounding the periphery of the underside of a patient’s nose |

|

the cushion includes ports for fluid communication with the patient’s nares… |

the cushion includes two openings for aligning with the patient’s nostrils |

|

a blower for delivering the gas to the mask |

a blower for delivering the gas to the mask |

|

a hose for connecting the blower to the mask |

a conduit for providing air of ambient pressure or above between the blower and the mask |

In view of the complete specification, the person skilled in the art would understand that any hose or conduit used in the system would be able to handle ambient pressure and above. The person skilled in the art would also construe the system being suitable for gas is equivalent to being suitable for air in this context.

Applying the double infringement test, all infringing embodiments of claim 2 of the parent would infringe claim 2 of the divisional; and all infringing embodiments of claim 2 of the divisional would infringe claim 2 of the parent. Therefore, the claims are considered to be for substantially the same matter and an objection would be raised.

In contrast, applying the double infringement test to claim 1 of the parent and claim 1 of the divisional would not result in an overlap objection to these claims. Claim 1 of the parent and claim 1 of the divisional are not considered to be for substantially the same matter.

Example 3

Parent

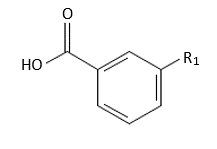

Claim 1: A compound of formula (I):

wherein R1 is a halogen atom.

Divisional

Claim 1. A compound selected from:

- 3-chlorobenzoic acid;

- 3-bromobenzoic acid;

- 3-fluorobenzoic acid; and

- 3-iodobenzoic acid.

The complete specification defines halogens as the closed group fluorine (F), chlorine (Cl), bromine (Br) or iodine (I). This definition would be understood by the skilled person and is consistent with the common general knowledge.

The person skilled in the art would construe the claim of the parent as a claim to four different compounds with each halogen being substituted at the R1 position. These are the same four compounds as in claim 1 of the divisional.

Applying the double infringement test, all infringing embodiments of the parent claim would infringe the divisional claim; and all infringing embodiments of the divisional claim would infringe the parent claim. Therefore, the claims are considered to be for substantially the same matter and an objection would be raised.

Example 4

Parent

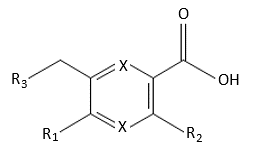

Claim 1: A compound of formula (II):

wherein:

X is CH or N;

R1 and R2 are independently selected from H, C1-6 alkoxy, C1-6 alkyl and halogen; and

R3 is a cycloalkyl, heterocyclyl, aryl or heteroaryl optionally substituted with one or more of C1-6 alkoxy, C1-6 alkyl, C1-6 haloalkyl, halogen, COOH, NH2, OH, CN, NO2, cycloalkyl, heterocyclyl, aryl or heteroaryl.

Claim 2: A compound of claim 1 selected from:

- 3-(1H-imidazol-1-ylmethyl)-benzoic acid (compound 1);

- 3-(2-pyrimidinylmethyl)-benzoic acid (compound 2);

- 3-(4-pyridinylmethyl)-benzoic acid (compound 3);

- 3-(3-pyridinylmethyl)-benzoic acid (compound 4); and

- 3-(2H-1,2,3-triazol-2-ylmethyl)-benzoic acid (compound 5).

Divisional

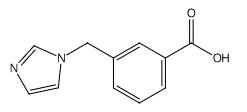

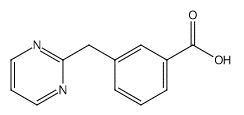

Claim 1. A compound selected from:

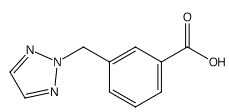

(compound 1);

(compound 2);

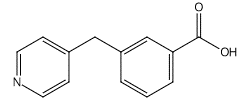

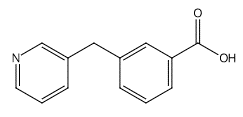

(compound 3);

(compound 4); or

(compound 5).

The closest claims identified in an initial assessment are claim 2 of the parent and claim 1 of the divisional. The assessed claims are directed to the same five compounds so are the same in scope, despite one claim providing chemical names and the other providing structures.

Applying the double infringement test, all infringing embodiments of claim 2 of the parent would infringe claim 1 of the divisional; and all infringing embodiments of claim 1 of the divisional would infringe claim 2 of the parent. Therefore, these claims are considered to be for substantially the same matter and an overlap objection would be raised.

In contrast, applying the double infringement test to parent claim 1 and divisional claim 1 would not result in an overlap objection to these claims. Claim 1 of the parent and claim 1 of the divisional are not considered to be for substantially the same matter.

Footnotes

- 1 Ganymed Pharmaceuticals GmbH and TRON-Translationale Onkologie an der Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Gemeinnützige GmbH [2021] NZIPOPAT 6 (“Ganymed”). Paragraphs [11] and [12] discuss not needing two patents for the same invention.

- 2 Regulation 23(2) of the Patents Regulations 1954.

- 3 Oracle International Corporation [2021] NZIPOPAT 5 (“Oracle”).

- 4 Patents Amendment Regulations 2018.

- 5 Ganymed, above n 1, at [21]-[33].

- 6 Oracle, above n 3, at [9].

- 7 Oracle, above n 3, at [8].

- 8 Oracle, above n 3, at [41].

- 9 Oracle, above n 3, at [7] and [39].

- 10 Abbott Laboratories [2003] NZIPOPAT 16.

- 11 Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research et al [2009] NZIPOPAT 21.

- 12 Ganymed, above n 1, at [170]-[171].